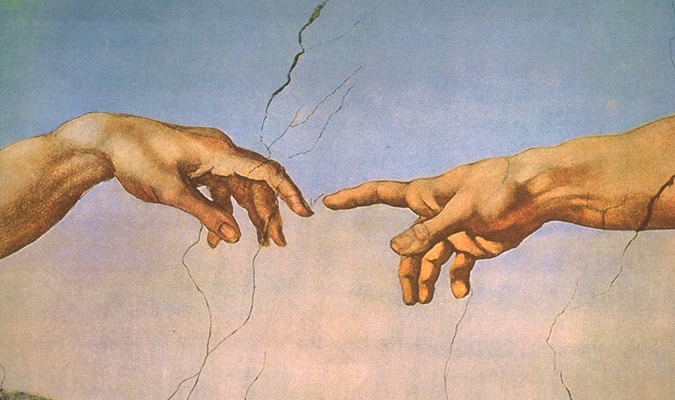

Our Week 4 Writing Activity: Re-write the story of Adam and Eve

Jennifer Wu:

Eve stared at her bare palms and slid her fingers over the dried blood stains on her arms and elbows. She blinked several times at the man next to her and looked at the trees around her before she coughed violently into a nearby bush. The man hit her back several times until she became very still. The man gently parted her lips open and blew air into her mouth. Together they stood up and wandered around, pointing at the different fruits, until they reached a tree taller and bigger than the rest. Its fruits had a strange orange color that glowed. Eve reached up and took hold of one of the fruits. She felt a small heartbeat pump gently against her palms for a few seconds before the man immediately shoved her to the floor. As she crashed to the ground, she torn the fruit from its branch. The blood stains on her arms gradually faded as the man howled and scrambled away. Eve slowly sat up and brushed off dirt from her back.

—

David Ngo:

Eve eyed the fruits above her as they blew against the wind. To take one in as a morsel let alone hold its color in her hands was of grave taboo. Yggdrasil was something to be revered, not trifled with. She wandered, with her silken hands caressing the top her head. This was it. This was the moment in which she could take action, something not Adam nor anyone else could ever think of. To be different was to be an outcast. Is that what she wanted?

With tricks of fate, a fruit fell down onto the roots of the holy tree. Eve’s temptations were beckoning. Grab it. Consume its gift. Her mind was being spoken to. Whether it be herself or that of another entity attempting to persuade her, she didn’t care. Eve, while innocent, was still cunning. She staggered across the green center that surrounded Yggdrasil, which was more lush than any other part of the garden. To know the consequences would not mean a concrete answer. But this was for a different future; one of curiosity, ruin, and perhaps recovery.

She went on to stand above the thing. No words could describe its color or shape. Eve checked her surroundings. Was anyone watching? Of course there was, but was Adam watching? Adam, her only companion. To sacrifice him would mean to lay things bare. She couldn’t begin to insult him with isolation, yet that was what she preferred compared to the likes of him.

She bent down, picking up the fruit ever so gently. She opened her mouth.

Crunch..

As she chewed, the taste changed: sour, sweet, bitter. While analyzing the flavors, she spotted a sillhouette. It was Adam.

“You did what was forbidden.”

“Yes, and now I will be forbidden as well.”

—

Jessica Bond:

Did I do it for love?

Did I imagine, when I reached my bare hand towards that green globe, the dew, the leaf, the bird that perched on the canopy, the stain it left on my fingertips as I touched it, how it burned, how the bird watched, the bird blinked and cocked its head, settling on a lower branch to listen in–did I imagine, did I see how the timeline stretched before me, behind, beyond to touch all that would succeed me, all that I would touch but would not see, not feel, not imagine, all the world stretch and flatten on God’s empty page, how the spaces would be filled, how the marks would be made, how my children would weep, how I would not weep for them, but continue to conceive, fill up the world with me, my images, my sons, my daughters not born, but already murdered?

Speak not, and forever hold my peace. My life did not end there, when I stood naked in that garden, my hand at the branch, my fingers touching the tabooed dew, my eyes beholding the green globe of knowledge that I would take into my body, that the sulphiric acids in my insides would dissolve into nothing, nothing, the knowledge promised not taken to build, but shat out the other end–I have sinned, Lord, yet I have learned nothing. No, as I touched that branch, allowed that red dew to stain my hands, I for the first time felt the cold wind, God’s breath upon my back, the bird-head cocked and listening then settling on the lower perch–I felt the feathers shiver, knocking the hairs out of my head–I am naked, I realized, naked and cold, my goose-flesh skin covered in sores, Lord, the sores I could not see but I would pass to my sons and daughters, great terrible gift of nakedness, of knowledge without foresight, of endless darkened paths.

Ashley Burnett:

He’s holding the apple in his hands and you’re wondering whether to take a bite.

On one hand, it’s innocent, right? It’s just an apple–no significance. On the other hand, you know after you take a bite that there’s no going back. That after you take the apple from his hands–so dry, the touch of it like a snake’s skin–that you’ll take everything else he offers you, too. And you know that Adam is waiting for you at home, no apples in hand, sitting in the garden. You know he never thinks about you with other men, because to him it’s like you’re the only two people on Earth. Almost as if you were made for one another, almost as if you were plucked from his rib.

You know that you’ll never be able to explain what you’re about to do, that it feels so significant as you reach across the table and feel the apple in your palm.

That’s right, there’s no going back. You open your mouth. You take a bite. You feel the juice run down your chin and you take another and another as you think up excuses. The apple tastes like nothing at all as you crush it against the roof of your mouth.

Miguel Olvera:

The apple, bright and tantalizing to the eye, went down smoothly. Eyes closed, I tasted the sweetness of the juice, now dripping down my lips, plump and shiny with the nectar we were forbidden from tasting. It feels good to defy God I thought and then I remembered–oh God.

I opened my eyes, and ran to Adam, feet smooth against the soft grass, running past the trees and the flowers, the sun setting behind me radiating hues of pink. A loud noise startles me (A voice inside my head–one I’ve never head before–whispers: thunder) and I fall and drop the apple. Adam, appears from behind some grapevines, his lips stained purple and sees the fruit on the floor.

Eve. He says, in disbelief. I look into his eyes and know he was waiting for me to do it first. So he would be blameless. So I allow him to try it too. He pretends to hesitate, but takes a bite without much need to convince. The light of the sun illuminates his cheekbones as his jaw moves powerfully up and down, and his eyes widen at the sweet taste. The pink sky turns the color of red, and from a distance, I hear the roar of a lion.

We hide from God, and the fruit feels heavy in our stomachs. I look at Adam and I see in his eyes the inevitable transformation and I can tell he sees it in me too. The discovery flesh. I see my dark skin and see Adam’s. We both recognize our newfound difficult knowledge, and the forthcoming loss of paradise.